Following on from the introduction of MetSwift’s predictive wildfire risk model in my last blog post, let’s look at some of its predictions for 2025 in the contiguous US.

Specifically, a few weeks and regions where notably higher risk is predicted on top of an already relatively high climatology.

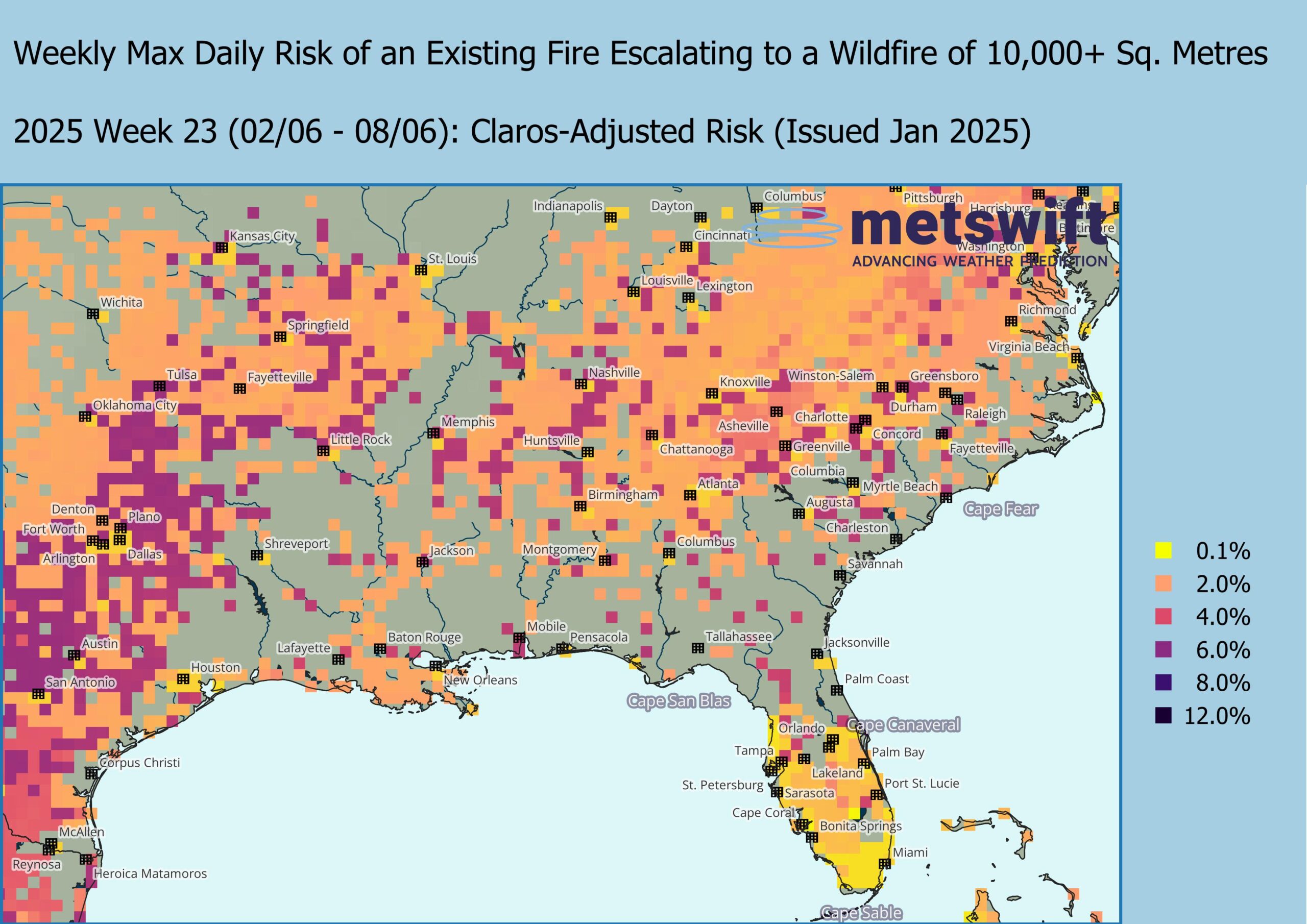

First up, early June in the south-eastern US.

Few will be surprised that to the east of Texas (where wildfire risk peaks within open forests), the climatological risk is highest within the predominantly oak and pine-oak forests that stretch from New England all the way to western Tennessee and the Missouri-Arkansas borderlands.

The secondary higher risk area of southern Florida is perhaps less intuitive. While there is plenty of herbaceous vegetation, the climate is generally humid, especially across the wetlands. However, less humid spells of weather do occur in a typical year, and it only takes a slight drying of that vegetation for its flammability to increase markedly.

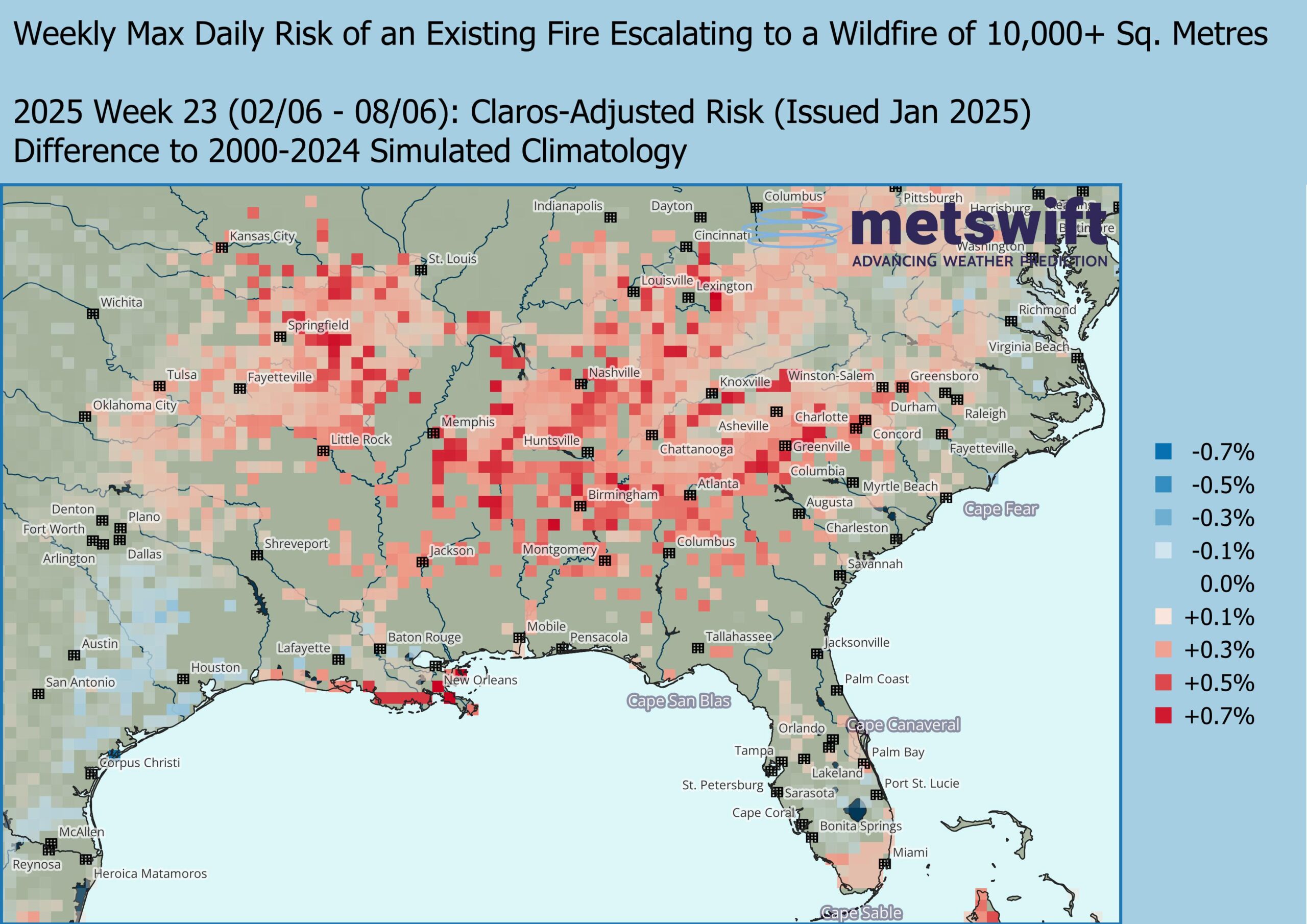

Early this June, the wildfire model suggests close to normal risk there, but in the forests to the north, it’s a different story, with the risk widely 0.3-0.7% higher than usual.

At face value, those anomalies may seem small but consider that the climatology is mainly about 2-6%. Proportionally, the predicted risk is 5-35% higher. Across the forest, this translates to a substantial increase in the probability of at least one wildfire.

A similar risk increase is seen for the herbaceous wetlands around New Orleans.

These increases are tied to Claros indicating both lower rainfall chances and a higher probability of daytime temperatures reaching at least 95°F (35°C) than usual. Plenty of reason to ensure that suitable contingencies are in place by late spring.

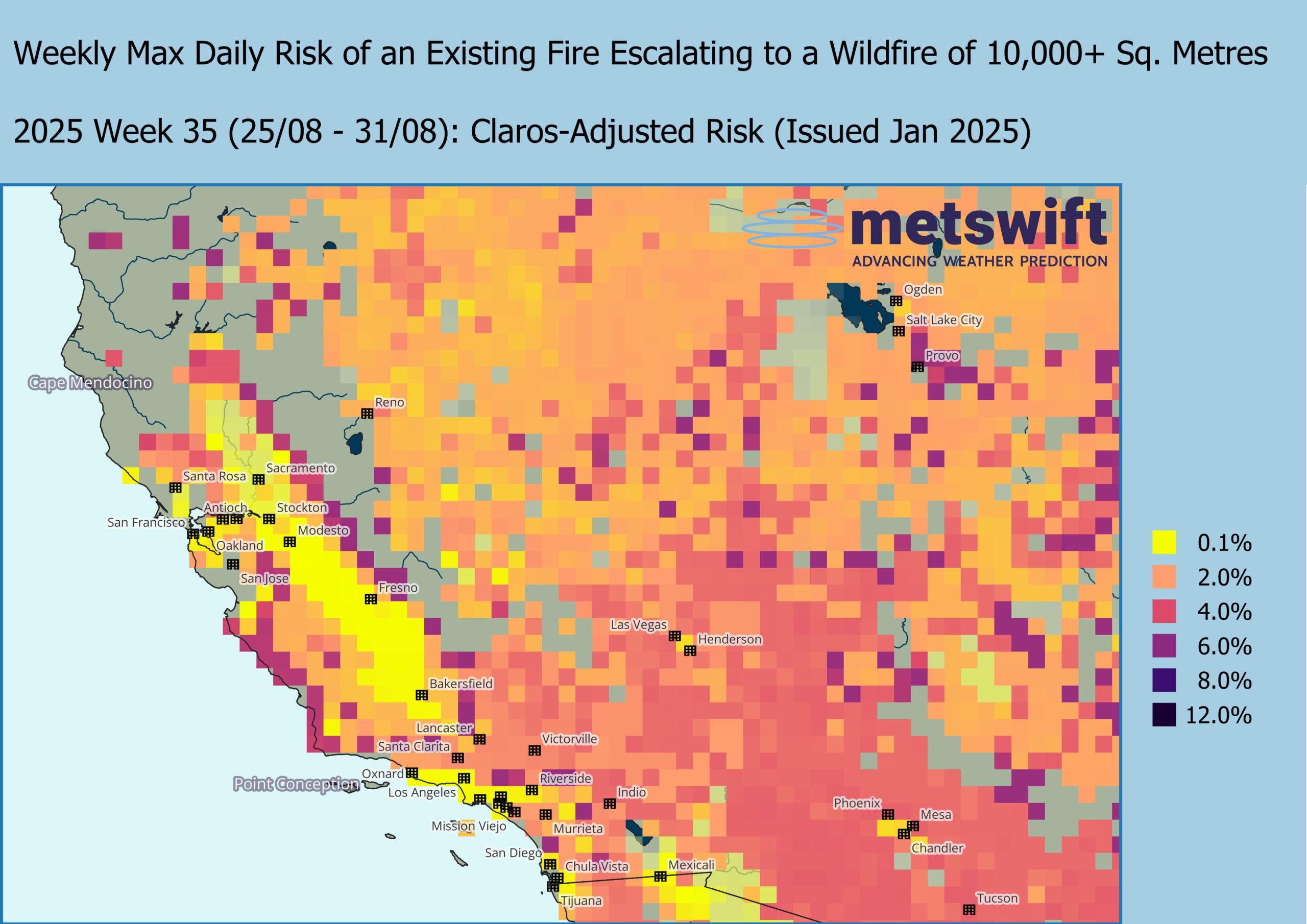

Twelve weeks later, attention shifts to the south-western US.

Here, wide swathes of herbaceous vegetation mingle with pockets of shrubland, adorning a highly rugged landscape famous for its dramatic peaks and canyons. The climatological wildfire risk is generally highest within the shrubland, especially where there is a modest slope that faces into the predominant wind (i.e. the air most often travels up the slope).

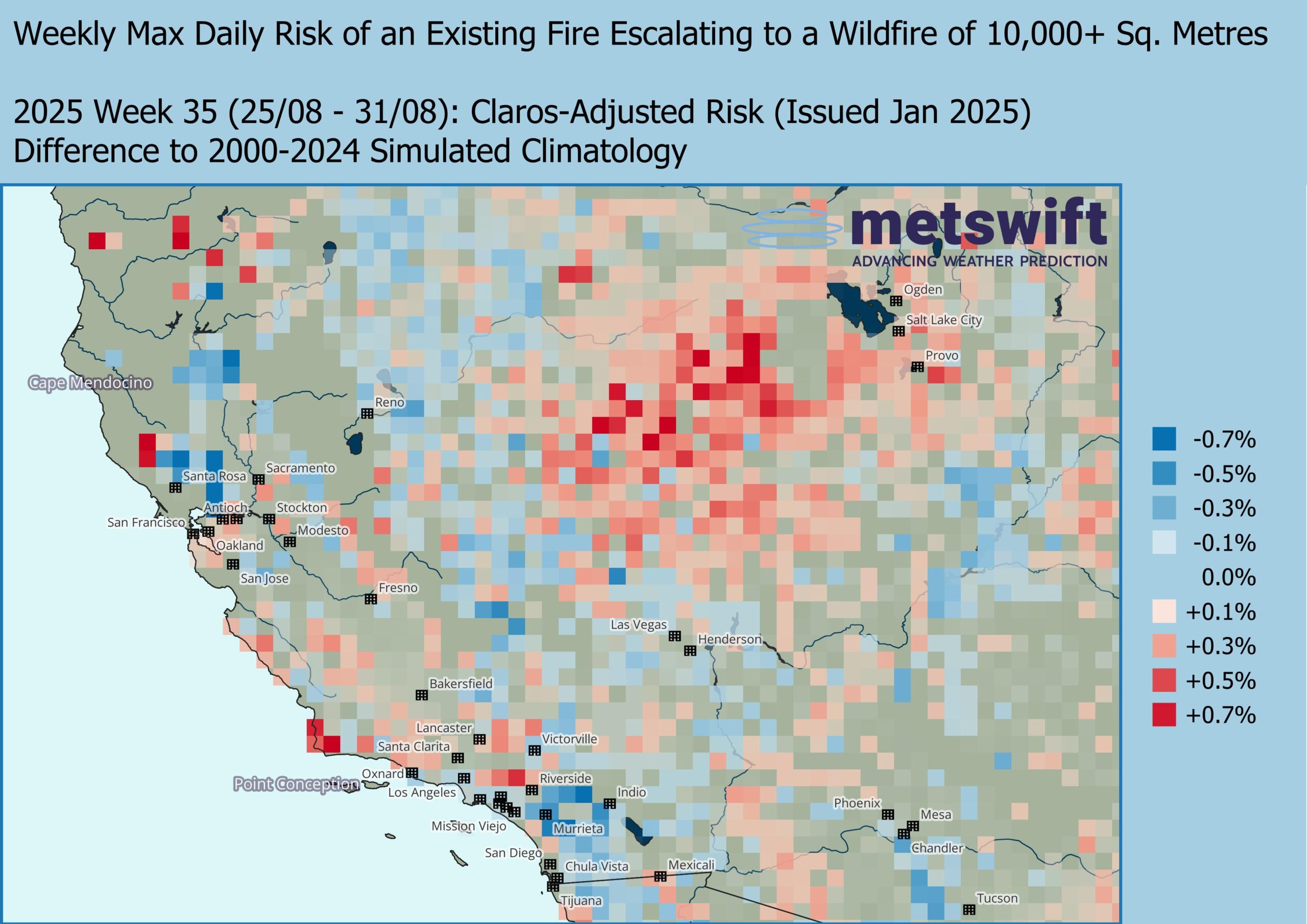

Claros suggests we should pay particular attention to the area north of Las Vegas and west of Provo during late August 2025.

Proportionally, the risk is around 5-35% higher than usual. While there is an ‘existing fire’ prerequisite, would you bet that not one individual will (accidentally or not) trigger a blaze somewhere within the region?

Again, this relates to Claros indicating below average rainfall chances (in an already dry climate) and above normal temperatures (increased chance of daytime reaching over 100°F or 38°C).

Note too, the patches of increased risk within the already high climatological risk zone along the Pacific coast. The approach to autumn (or ‘fall’ to the locals) sees the wildfire season begin to enter its peak stage. Claros suggests even hotter weather than usual with a raised chance of at least 110°F (43°C) being reached somewhere in California.

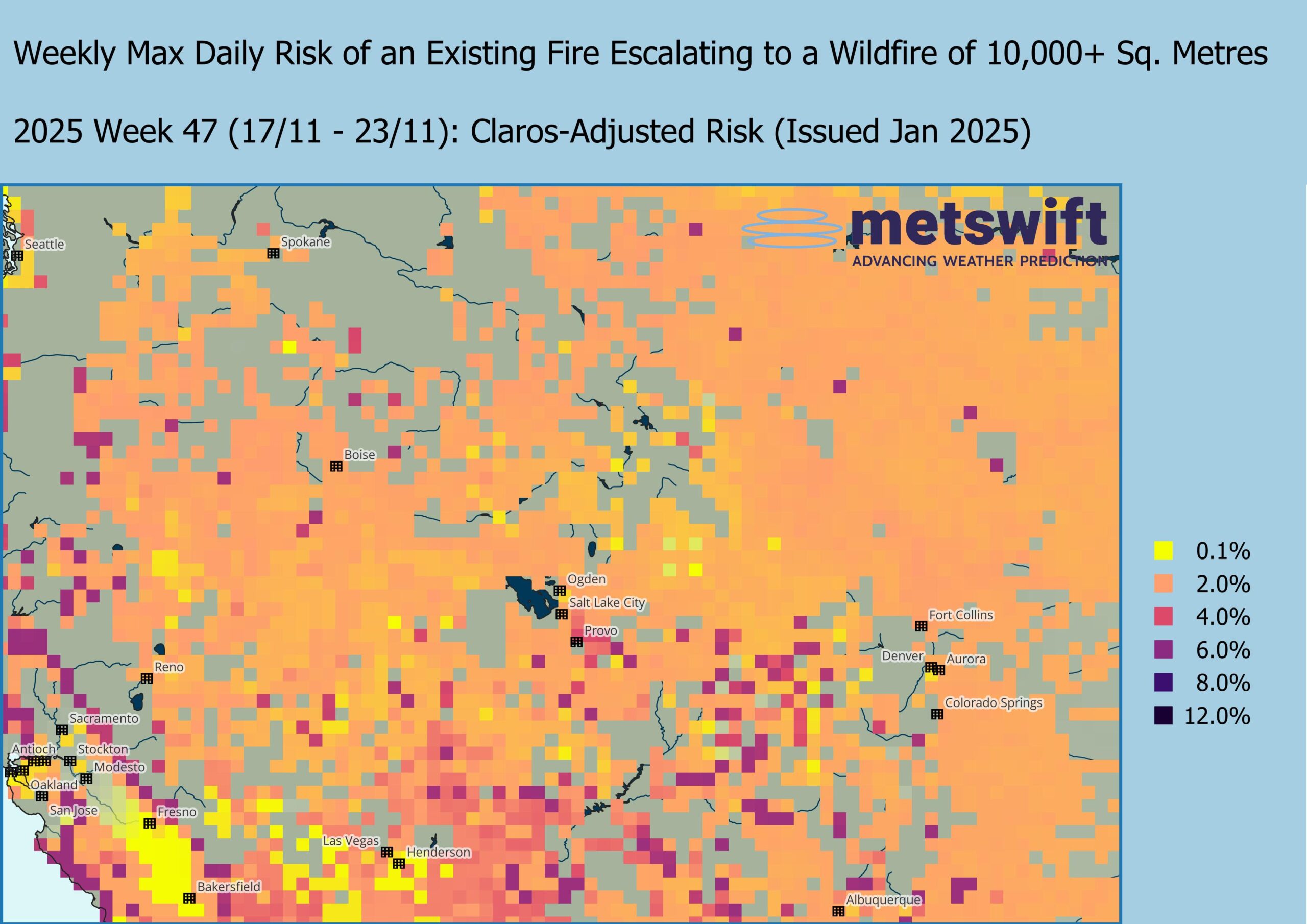

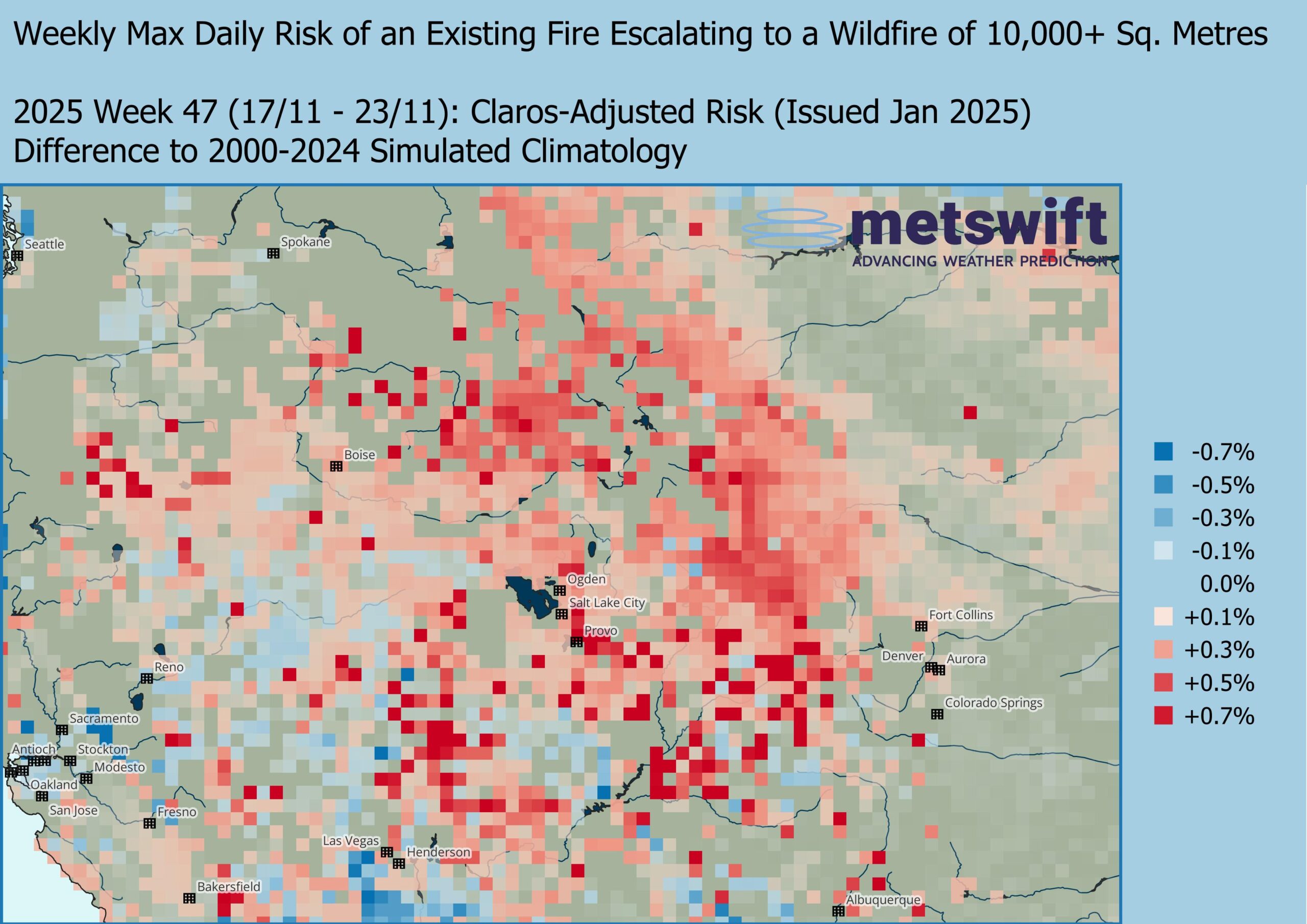

For the final standout of this blog entry, we look to the north and slightly east, another 12 weeks later in the year.

Again, this is a rugged landscape largely covered with herbaceous vegetation and patches of shrubland, but here there are also some swathes of forest in the mix. Composed mainly of needle-leaved evergreens, these forests have relatively low wildfire risk compared to the herbaceous vegetation, while shrubland generally has the highest risk.

Claros suggests that unusually high risk will span a startlingly large area during mid-late November 2025.

This time, it’s mainly down to a combination of increased risk for both high wind speed and high temperatures (for the time of year; daytime highs in the 70s °F or 20s °C) in Claros’ guidance, rather than reduced rainfall.

Generally, increased preparedness and vigilance is advised if you’re going to be anywhere in central Montana, southern Idaho, central or south-western Wyoming, much of Utah, or western Colorado within that week or close to it.

Hope for the Best

As unsettling as those high and increased risks may be, it’s worth keeping in mind that this is all probabilistic. These wildfire risks are in part derived from the probability of certain weather conditions occurring, rather than a single predicted weather scenario. The rest is down to terrain characteristics such as land cover and slope.

Meanwhile, the socioeconomic impact of a wildfire depends heavily on what’s burned. With the early 2025 fires in south California, we sadly witnessed the high end of the spectrum, with at least 25 deaths and over 12,000 structures damaged or destroyed as of 16th January 2025.

Let’s hope that proves to be by far the worst that will be endured for many years to come.

Be sure to look out for my next blog, which casts an eye beyond the US.

James Peacock MSc

Head Meteorologist at MetSwift

Featured photo by Mike Newbry on Unsplash