There’s nothing quite like a blanket of snow for transforming the landscape into one that captures the imagination. In some parts of the world, that effect soon wears off as the snow sticks around for weeks, even months. Not in the lower reaches of the UK and Ireland, that’s for sure. While some there disapprove of it regardless, there are many who find it encaptivating, owing to its scarcity.

How terribly often it “almost snows” – that stinging cold rain that hurts both physically and psychologically – or does snow, only to not settle. Then there are those mornings where you wake up to a brilliant covering, only for it to be gone within a couple of hours.

For this blog, I’ve set about investigating how infrequent lying snow truly is in the UK and Ireland during the months of November through April.

I’ve selected locations spread right across the UK and Ireland that are mainly in population centres. For anyone wondering, Warrington was chosen as a midpoint between Liverpool and Manchester.

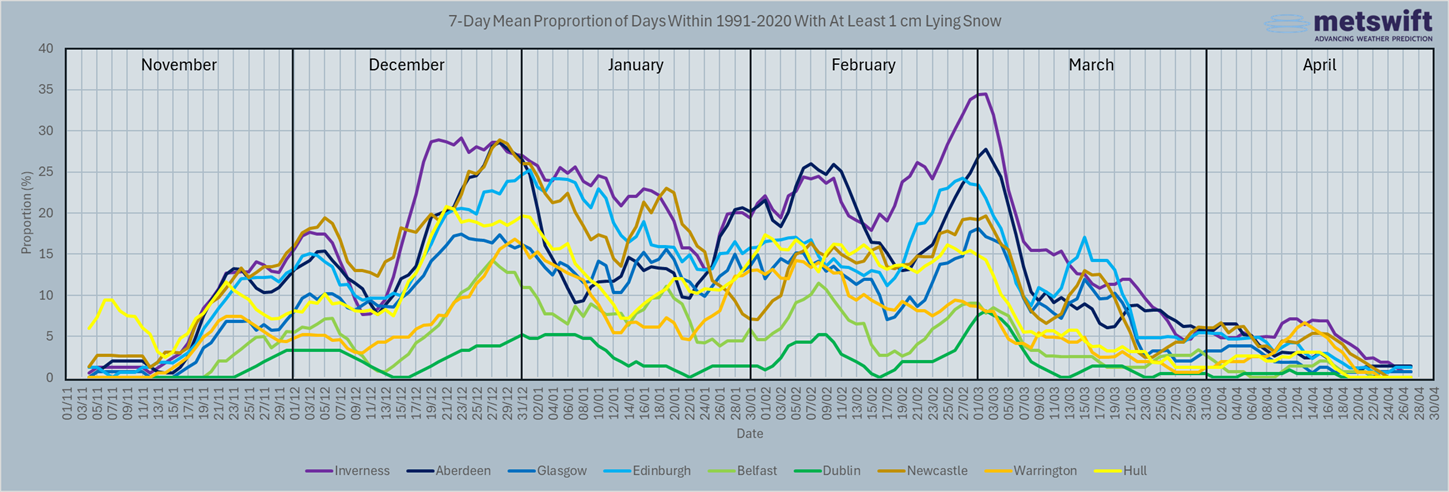

Northern Half of the UK and Ireland

Overall, we can see an unsurprising pattern across the locations and months. The lying snow frequency generally increases as you look northward and eastward. It starts out very low until mid-November, after which most places are within a range of 10-20% most of the time until mid-March. Interestingly, the popular statement that snow is more likely at Easter than Christmas is not supported here.

Peering closer unearths some intriguing details:

A sharp increase for the Scottish locations plus Hull during the mid-stages of December

With this being more pronounced the further north and east you look, this is likely down to the seasonal cooling trend, especially in the seas around the UK.

A decrease over time across most of January in Inverness and Edinburgh

This one is harder to explain without investigating other metrics like rainfall. It could be associated with a trend toward drier weather, on the basis that lying snow rarely sticks around for very long at low elevations even in Scotland. It certainly won’t be temperature related, as those typically reach a minimum between approximately mid-January and mid-February.

A considerable peak late February into March for the Scottish locations

Another fascinating find. A plausible explanation is that this is down to an overlap of the increasing chance of snowfall due to cooling seas with the time during which the sun’s influence isn’t yet strong enough to make snowfall much less likely.

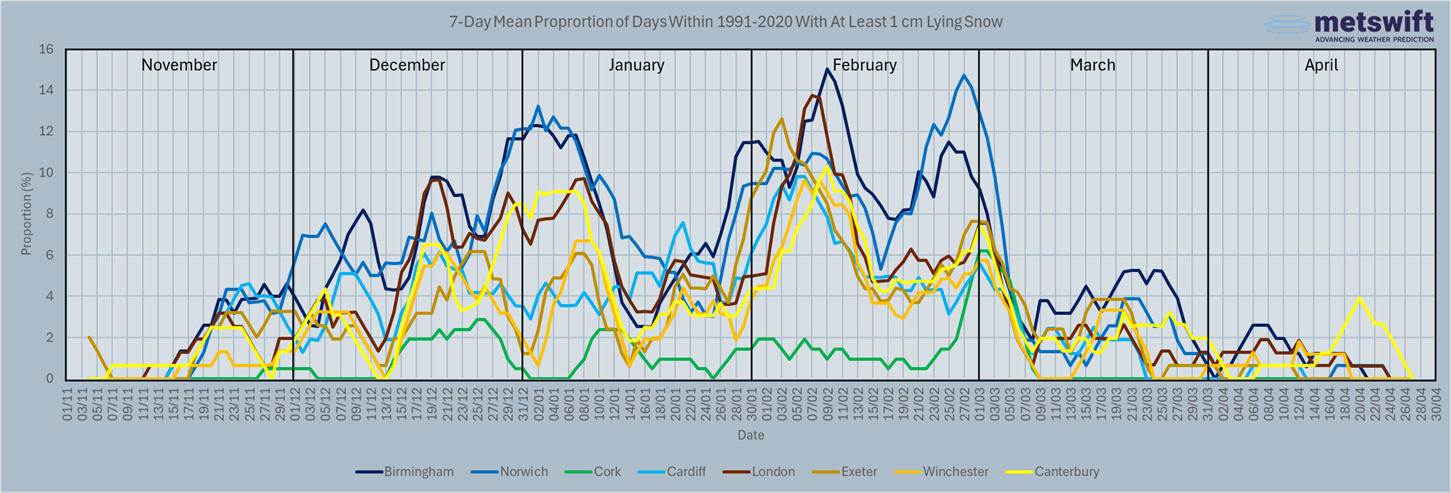

Southern Half

It won’t come as a shock that the frequencies here are lower than in the northern half. We still see the general increase when looking north and eastward. These graphs also make clear how very rare lying snow is for lowland coastal locations in Ireland.

The pattern over time is similar to that for the north half, except that the November increase begins slightly later, and the March decrease a bit sooner. Also unsurprising, considering a warmer climate.

Within the months, we see some of the patterns noted for the northern half, along with a few new ones:

A pronounced late December into January peak for Birmingham, Norwich, and Canterbury

This likely has a similar cause to the mid-stages of December increase seen for the Scottish locations and Hull. However, for Canterbury in the southeast corner of England, there’s probably more dependence on cooling of the land rather than seas. This is the region of the UK most readily affected by cold airmasses over continental Europe.

Another prominent peak in the first half of February for all but Cork

This tends to be when some of the coldest weather of the winter occurs in the southern half of the UK. Though the days are lengthening swiftly, the seas continue to cool, and this usually dominates until mid-late February. Even so, I’m not certain that this peak in lying snow frequency is wholly down to that. There may well be a role played by weather patterns, as the month tends to turn drier later. Snow-wise, it doesn’t matter how cold it is if nothing’s falling from the sky!

A rebound of frequencies during mid-March in Birmingham and Norwich

This one is particularly intriguing. Temperatures are usually on the rise by this time, but freezing weather remains possible. Meanwhile, increasingly strong sunshine makes ‘diurnal moist convection’ more likely. That’s when (indirectly) sun-warmed air rises and cools enough for its moisture content to condense into precipitation-bearing clouds. In March that usually starts out as snow as it departs the cloud.

A key trait of diurnal moist convection is that it can produce both heavy precipitation and downdrafts. Rapid descent of cold air from aloft can be sufficient to keep precipitation as snow to low elevations. This is why you can see showers in March that bring rain, sleet, and snow (or soft hail; graupel). I suspect the slightly higher lying snow frequencies are related to that.

A peak around 20th April in Canterbury

This seems rather peculiar at face value, but some sense can be made of it. The peak is a mere 4% and seen at only one location. Odds are, this is down to coincidence rather than a true trait of the weather.

The ‘Magic’ of Snow in the UK & Ireland

Even in the snowiest location analysed above, the 7-day mean frequency never exceeds 34%. That’s at least 1 cm of lying snow once every three years on average. For many places it’s less than once every four years most of or all the time. What’s more, the trend has been downward in recent decades, lying snow an increasingly rare sight.

No wonder, then, that there are many ‘snow enthusiasts’ in the UK & Ireland, who rejoice at the sight of it. Some see the positive side even when such weather causes significant disruption. In low-lying areas, particularly of the south and Ireland, lying snow is rare enough to seem novel on occurrence.

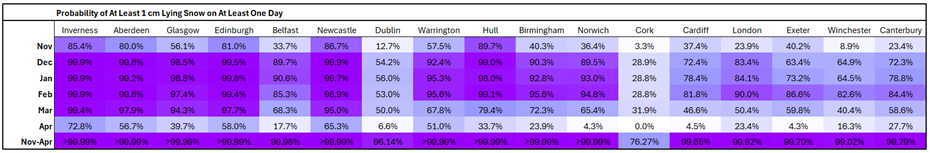

Yet believe it or not, statistical theory suggests it’s very rare for all of November through April to pass without most of the country seeing at least 1 cm of lying snow at some point. Finding the estimated probability of that is simply a matter of multiplying all the daily probabilities of less than 1 cm lying snow together. Subtracting that from 100% gives us the table below, for which this procedure has also been applied to each calendar month.

This is what happens when you’re looking at an event occurring at least once within 181 days. It only takes a small average daily probability for the odds of avoiding it completely to become miniscule. Even for periods of 28-31 days, we can see how much the likelihood escalates.

That said, there’s reason to believe that this doesn’t paint the true picture.

Statistical Limitation

The theory applied above assumes that the probability of lying snow on any one day has no connection with that on any other day. In practice, we know this isn’t true. For one thing, lying snow can carry over between days. In fact, extensive snow cover can lower near-surface air temperatures, helping it to remain in place. For another, falling snow often occurs in a clustered manner, with multiple days affected during a single cold spell.

The net effect is likely an overestimation of the probability of at least one day seeing at least 1 cm lying snow. For example, processing the daily data for Birmingham into a binary ‘did’ or ‘didn’t’ format tells me it happened in 26 of the 30 winters 1991-2020. That’s a frequency of 86.7% rather than over 99.99%. Concerningly for snow enthusiasts, the four times it didn’t happen were all in the past 11 years. By remarkable coincidence I get the same 86.7% frequency for London, but without the recent clustering of winters where it didn’t occur.

No Stranger to Snow

Even the truer frequencies mentioned above still equate to about 17 in every 20 November-Aprils seeing at least one day with at least 1 cm lying snow. In the heavily built-up areas of Birmingham and London, no less. Considering this, it may seem ludicrous that transport networks in lowland UK are often disrupted by even small accumulations, but that has more to do with the scarcity of deep, long-lasting snow. For small, relatively scarce amounts, paying out for snow tyres (or chains to attach) and snow plough services is unlikely to be worth the investment.

I’m sure there will be some readers who feel sure that snow is less frequent local to them than indicated here. Those living in low-lying areas, especially near the coast, may well be correct. In fact, I’m pretty sure I live in one such location, having directly observed at least 1 cm in only around half of the past 20 years. Don’t move to lowland Dorset if you like snow!

The Long-Term Trend

It would be remiss of me to write about lying snow frequency without discussing the long-term trend. As I posted on social media early in December, conditions conducive to snowfall are becoming scarcer in the UK. This will be true in Ireland too.

This will not come as surprise to many – I’ve spoken to plenty of the older generations who have talked of more frequent snow during their youth.

The UK and Ireland have a strongly maritime climate in which conditions conducive to snowfall to low elevations tend to be only just cold enough. This means that even a slight change in the long-term mean temperature can have a substantial impact on snow frequency.

Being only just cold enough can make for a climate in which heavy snow events feature regularly. The colder air is, the less moisture it tends to contain. You may have heard the phrase “too cold to snow”. This only really becomes true in extremely cold conditions – approaching -40°C! – but it has some relevance in places like the UK. We’re more familiar with heavy, ‘wet’ snow events than the dry, powdery sort that takes a while to build up. That’s what occurs more often when temperatures are at least a few degrees below 0°C.

The climate of the UK and Ireland has warmed enough in recent decades that now, events that would once have been only just cold enough are now slightly too warm for snow.

As with almost everything, there are winners and losers from this. Reduced disruption due to snow (and ice) benefits many, but a drop in snowfall days even up in the mountains has given some ski resorts a hard time. Psychologically, some rejoice at the scarcity of hazardous outdoor conditions, while others find winter more of a mental challenge without the visual spectacle of lying snow.

However it affects you, I hope that somewhere you can find some cheer during the shortest days of the year.

James Peacock Msc

Head Meteorologist at MetSwift

Featured photo by the author, taken at 8:14 on 1st February 2019 on the outskirts of Fordingbridge, England. Most of the snow cover was gone by the afternoon!